A Brief Investigation of Ontario’s most Expensive Undergrad

One undergraduate program in Ontario costs more than all the others. I wanted to know why. Here is the answer.

Ontario’s Ivey League

The Richard Ivey School of Business (Ivey) is part of Western University in London, Ontario. Compared to other bachelor’s programs at the university, Ivey’s annual tuition is twice that of the next most costly option and four times that of most programs:

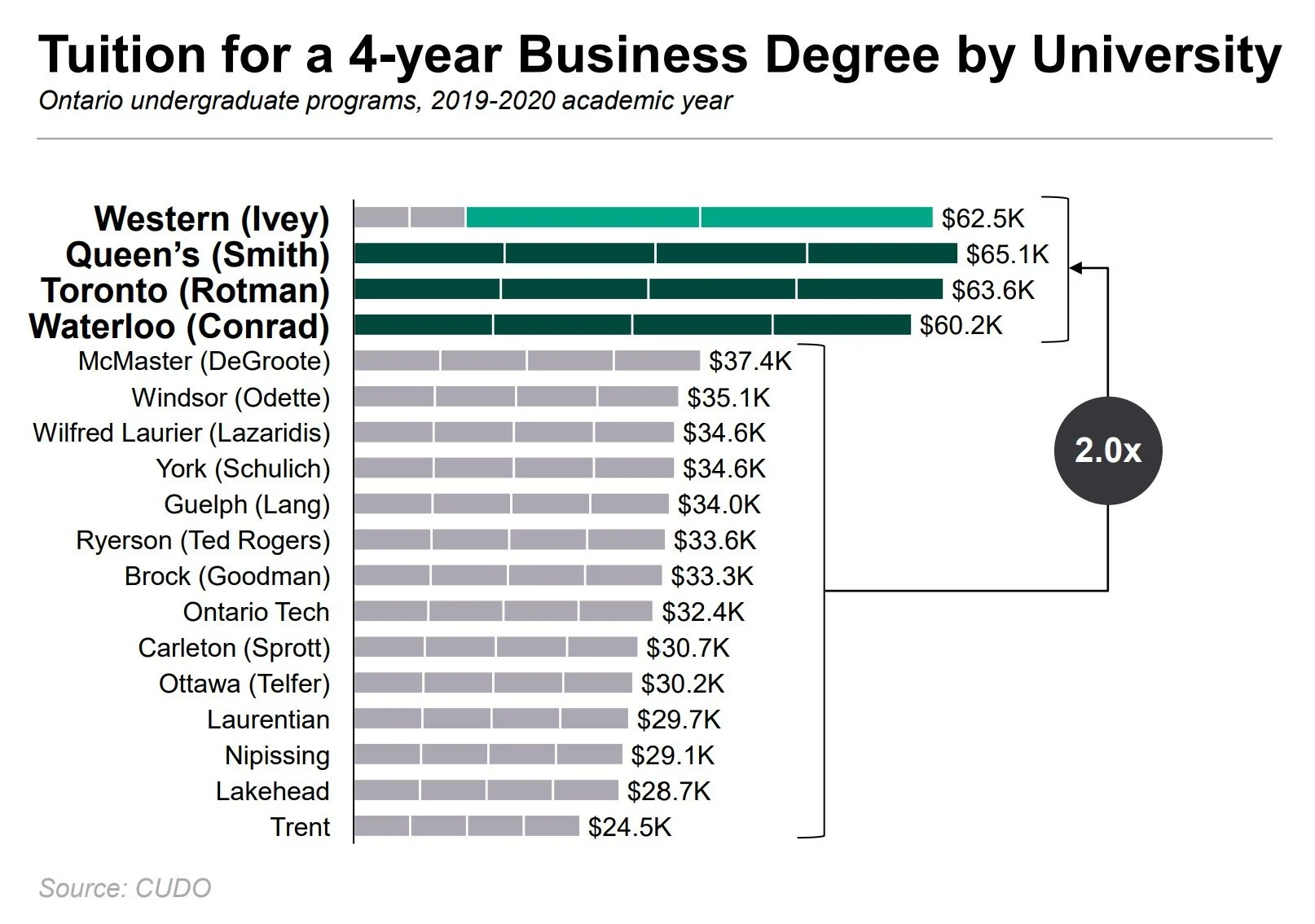

Compared to business programs provincially, a year at Ivey is three times mores expensive than most Ontario universities:

In addition to Ivey, Smith at Queen’s University, as well as Rotman at the University of Toronto and Conrad at Waterloo, have notably high tuition. When you factor in that Ivey is a “second entry” program (meaning students spend the first two of their four years in another faculty), these exceptionally priced business programs are exceptionally similar in price:

While the price of a degree is comparable across these four schools, Ivey is still unique. Being responsible for just the last two years of an undergraduate’s degree (and concentrating the higher tuition to just those years) disproportionately increases the program resources Ivey has per student.

Nuance aside, today there are four business schools where a degree costs twice what is does elsewhere in Ontario. Looking at the oldest readily accessible data (from the 2006-2007 academic year) confirms that this isn’t a new phenomenon:

Which brings us back to our question, why?

And, in a province where universities receive significant public funding, how?

The Ballad of Harris & Tapp

Starting in the 1960’s, Ontario tuition policy put an effective cap on what schools could charge students. The cap was reassessed annually, allowing for limited increases. While schools were under no obligation to take full advantage of the increases, almost all did. Tuition across the province was relatively undifferentiated.

For decades, this was the paradigm used to balance two competing policy goals:

Ensure universities had sufficient revenue to finance quality education

Ensure university education was sufficiently accessible

Lawrence Tapp declared it “out of touch with today’s reality”.

In 1995, Western’s business school (soon to be Ivey) hired Tapp, the first non-academic dean in its history. A Canadian businessman known for leading an international packaging company, Tapp saw business schools as part of a global marketplace. He believed that current policy ignored how universities competed globally for star faculty members, just as graduates competed globally for jobs at top companies. Without intervention, Canada would be left behind.

As such, Tapp defined “quality education” as competitive with the best schools in the US and abroad. He endeavoured to deliver such an education at Ivey.

To do that, he needed money.

Knowing fundraising could only go so far, he and likeminded peers at other universities lobbied the government for flexibility to charge higher tuition. Their timing was perfect.

The year of Tapp’s appointment, Mike Harris became Premier of Ontario, elected on the promise of a balanced budget via small government. Universities raising revenue through increased tuition, rather than increased provincial funding, fit neatly into his agenda. In 1998, three years after Tapp and Harris took their respective posts, “additional cost recovery” (ACR) programs were introduced and the paradigm of tuition in Ontario shifted.

The ACR concept was simple: allow universities to boost revenue through select programs that were either (i) expensive to operate or (ii) provided graduates with distinctly high-earning potential. For the programs that qualified, tuition could be raised to any level. The only condition was that a fixed share of the new revenue had to be set aside for financial assistance to support accessibility.

Undergraduate business was on the list of ACR programs. Lawrence Tapp didn’t miss a beat. The data suggests his peers at Smith and Rotman didn’t either.

In 2003, a new government took power, freezing tuition and ultimately reregulating all programs. Critically, however, there was no reversion of the ACR changes. Future tuition increases were to be based on the fee level charged in the 2003-2004 academic year. The differentiation was locked in.

Lawrence’s Legacy

The impact of the ACR changes is profound. As an illustrative example, let’s compare Schulich at York with Rotman at the University of Toronto.

Since ACR, both schools have made the maximum tuition increase allowed under policy in every year for which we have data. As such, both have almost doubled tuition between 2006-2007 and 2019-2020. But for Rotman, that doubling means an additional $7.6K, whereas at York it’s only an extra $4.1K:

The differentiation is compounding. And not just numerically.

At the peak of his lobbying, Tapp wrote an op-ed laying out his vision for what tuition deregulation would enable over time:

“University education exists within a virtuous circle. Schools that attract the best students from around the world also attract internationally renowned faculty – individuals who are voracious in the pursuit of new knowledge and the most committed to teaching seek the best students.

These schools can charge high tuition fees because of the perceived value of their degrees whose graduates command the highest salaries from the most sought-after corporate recruiters. These graduates in turn create an elite network of alumni from the corporate and professional worlds that further increases the school's attractiveness and broadens its funding base.”

Data confirms that donations have broadened the school’s funding base relative to other university programs. The last year Ivey published numbers independent of Western (2013-2014), Ivey’s donation revenue per student was almost 5 times higher than the rest of the university:

Data also confirms that (for the most recent class with comparable data) Ivey graduates commanded higher salaries relative to their peers:

And we’ve already seen the data on charging higher tuition fees.

So, to our questions:

Why is Ivey more expensive? In the 1990’s, Ivey appointed a businessman as dean. The economy was globalizing. Competition was growing more intense. In pursuit of Ivey and Canada’s international relevance, he looked to increase the school’s resources via higher tuition.

And, how? This dean and like-minded peers lobbied the provincial government. Their views fit with that government’s ideology. A program was introduced to allow higher tuition. Ivey was among the schools that increased tuition before the program was discontinued.

That’s the story. Naturally, an expensive school raises questions of accessibility and elitism – the vices of Tapp’s “virtuous circle”. I won’t address those here, but I will share prompts on a few issues that I find uniquely interesting / important:

There is a tension between creating equal opportunity and nurturing individual exceptionalism. Where do you feel that the balance should lie in education? Does this change for different fields of study? For different age groups?

The risk when you create a pipeline to power and influence (especially when you charge extra for it) is that power and influence become entry requirements. An elite school becomes an elitist one, where graduates likely to be future leaders are, to borrow from Tapp, “out of touch with today’s reality” (e.g., the folks who set hourly wages are unlikely to have ever earned hourly wages). How can we avoid this undesirable outcome?

Business schools teach students to succeed in systems that measure success in terms of money. As such, business schools create societal value in scenarios where money is a good proxy for value creation. Where is money a poor proxy for value creation? What does this mean for business schools?

In the spirit of university education, these questions are left as an exercise for the reader.

---

A special thanks to Andrew M. Boggs. We’ve never met, but more than a decade ago, while pursuing your PhD at Oxford, you wrote a journal article without which my questions would have been unanswerable.

If you enjoyed, consider copying the page link and sending it to 2 people. It’s like a multi-level marketing scheme, but for reading. 📚